Chesapeake Bay Dead Zone Conditions Improved in 2020

Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the United States and the third largest in the world, is particularly vulnerable to human impacts and has been severely affected in recent decades. Chesapeake Bay’s “dead zone” is an area with little to no oxygen where fish, shellfish, and crabs are often unable to survive. The size of the dead zone reaches its peak during summertime and is one of the major water quality concerns facing the Chesapeake Bay.

The Blue Crab is one of Chesapeake Bay’s native aquatic species that suffers from lack of oxygen in the Bay’s dead zone.

A dead zone forms when excess nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorous from fertilizer and agriculture, enter the water through runoff and fuel algal growth near the water surface. When these algae die and sink, their decomposition uses up dissolved oxygen from the bottom water. Scientists refer to these oxygen-poor waters as “hypoxic,” meaning oxygen concentration is less than 2 milligrams per liter, which is too low for aquatic organizations to thrive.

2020 Report Shows Second Smallest Chesapeake Bay Dead Zone in 35 Years

In collaboration with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Anchor QEA helped develop and now manages a real-time Chesapeake Bay Environmental Forecast System computer model that forecasts environmental conditions in the Bay every day. Results from the computer model were used to develop the 2020 Chesapeake Bay Dead Zone Report, summarizing the severity of the dead zone over the summer, compared to the last 35 years and the last 5 years.

In 2020, several factors contributed to improved low-oxygen, or hypoxic, conditions, including cooler temperatures and a large summer storm.

The size of the dead zone in 2020 was estimated to be on the low end of the normal range for 1985 to 2019, with less hypoxic water this year than in the past 5 years. These conditions were due to a cooler spring and fall, a hurricane during the summer, and continued efforts to reduce nutrient runoff. Cooler water can hold more oxygen and slows the rate at which bacteria in bottom waters remove oxygen through respiration. Additionally, windy weather helps mix and aerate the water. The combined effects of cooler temperatures and winds resulted in hypoxia beginning later than in previous years.

Cool Temperatures and Wind Events Lead to Below-Average Hypoxic Volumes

The Chesapeake Bay experiences hypoxic conditions every year, with the severity varying from year to year, depending on temperature, wind, and nutrient and freshwater inputs. In spring 2020, nutrient supply to the Bay suggested that hypoxia should have been only slightly better than average for the year. But overall hypoxia levels were actually quite low and the duration quite short. This demonstrates how a cool spring and a large summer storm can impact the severity of Chesapeake Bay hypoxia from one year to the next.

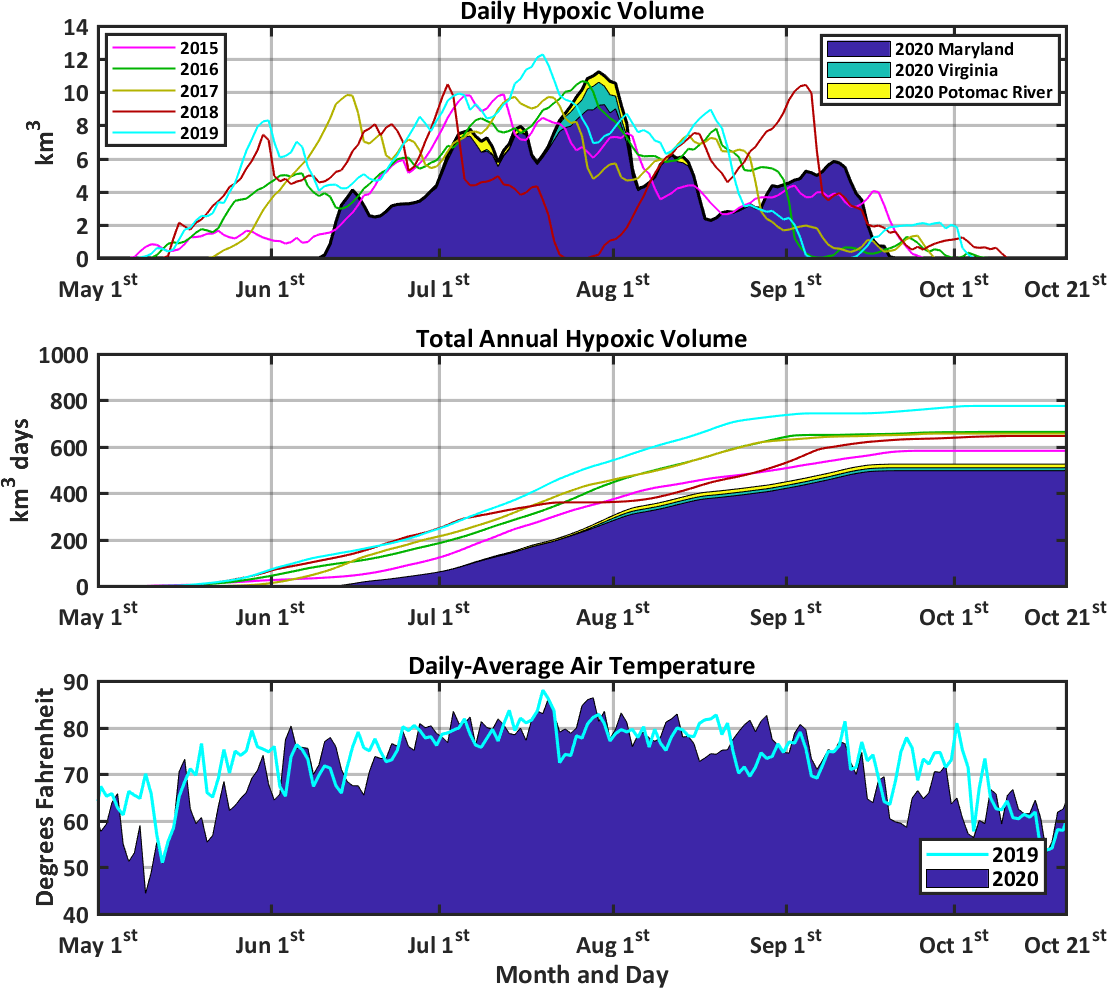

Graphs from the 2020 Chesapeake Bay Dead Zone Report illustrate the hypoxic volumes for 2015 to 2020 and air temperature over the Bay for 2019 and 2020 for the months of May to November. Note the cooler temperatures in May 2020, with later onset of hypoxia, in addition to the decrease in hypoxia starting at the end of July 2020, in response to Hurricane Isaias.

Even though the amount of hypoxia was quite low in 2020, when evaluated over the entire summer, the maximum volume of the Bay experiencing hypoxic conditions on any given day was quite high. The height of 2020 Chesapeake Bay hypoxia occurred in July, after a spell of weak winds and high temperatures pushed the total hypoxic volume to 11.2 cubic kilometers—equivalent to 4,480,000 Olympic-size swimming pools. However, in early August, hypoxia decreased rapidly in response to Hurricane Isaias, before returning to peak again in September.

Ultimately, even despite long-term warming temperatures, hypoxia is decreasing as a result of watershed-wide Chesapeake Bay cleanup efforts to improve water quality, including reducing pollution, restoring habitats, managing fisheries, protecting watersheds, and fostering stewardship through communication and outreach programs. Taking into account the transient weather conditions and summer storms, the 2020 hypoxia report continued to show lower volumes in recent years. This smaller dead zone means more areas for oysters, crabs, and fish to thrive in the Bay for future years to come.

Continued Water Quality Forecasting

Anchor QEA continues to collaborate with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science to forecast water quality throughout the Chesapeake Bay daily. A completely automated system forecasts salinity, water temperature, and acidification, in addition to dissolved oxygen and hypoxia. In early 2021 Anchor QEA will lead the transition of the forecast system to a higher-resolution computer model grid to improve accuracy. The goal is to use the improved computer model to forecast hypoxic conditions in summer 2021 and then evaluate the severity of hypoxia at the end of summer.

Read the entire 2020 Chesapeake Bay Dead Zone Report published by Anchor QEA and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science here.

News Reports on the 2020 Chesapeake Bay Hypoxia Report

Virginia Institute of Marine Science dead-zone report card reflects weather, improving water quality

CBS Local – Chesapeake Bay Dead-Zone Conditions Reduced ‘Considerably’